June 30, 2020

Helping employees overcome challenges posed by the communities in which they live, work and play can improve their health and performance, reduce health disparities and position your organization as an employer of choice.

Improve Employee Health and Well-being

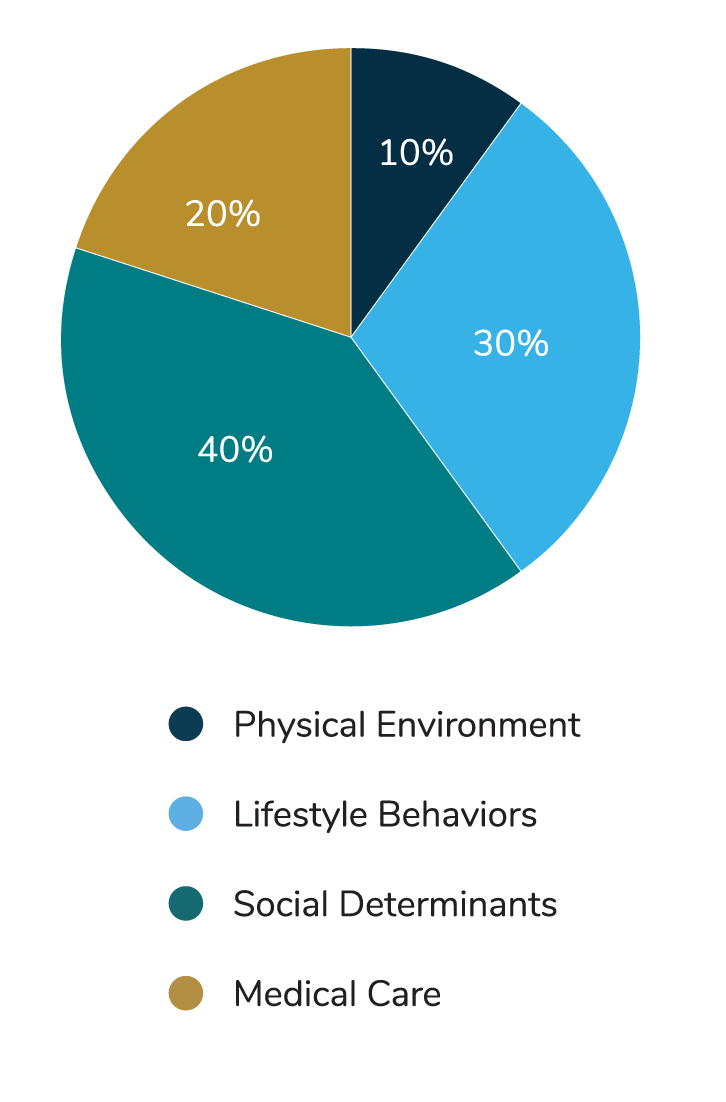

By some estimates, social determinants influence 40% of our overall health status —more than medical care or lifestyle behaviors alone.1 Indeed, there is a large body of evidence showing causal relationships between social factors like income and education and a multitude of health outcomes.2 Social factors affect health in several ways, including by:2

- Impacting it directly (e.g., pollution and allergens can exacerbate asthma);3,4

- Influencing health-related behaviors (e.g., a lack of grocery stores or parks can affect food choices or activity levels);5,6

- Causing physiologic changes in response to chronic exposure to social and environmental stressors (e.g., the stress of lower income can contribute to higher blood pressure); and7,8

- Affecting the way genes are expressed (e.g., educational attainment and occupational class have been linked to changes in telomere length).9

Because social barriers have a large bearing on our health, behavior change programs and medical benefits offered by employers may prove ineffectual if social determinants aren’t also addressed.10

Reduce Health Disparities

Health disparities are often rooted in social and economic disadvantages and exacerbated by differences in social and built environments; socioeconomic and living conditions; and access to and use of quality health care services for different populations and geographies. For example, people of color and low-income earners are more likely to be uninsured, face barriers to accessing care and have higher rates of health conditions compared to their white counterparts or those who earn higher incomes.10 And those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, agender or asexual (LGBTQIA+) have worse health outcomes than their heterosexual counterparts, with data showing that they have a higher risk of cancer and mental illness and are more likely to smoke, drink alcohol, use drugs and engage in other risky behaviors.11 People who identify as LGBTQIA+ and are a member of a racial or ethnic minority often face the highest level of health disparities.11 In many countries around the world, certain groups have substantially worse health indicators, especially when it comes to life expectancy, mortality, prevalence of diseases or access to health services.

What Are Health Disparities

Health disparities are defined as differences in health and health care quality and access between population groups. Disparities can occur across race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, age, location, gender, disability status and sexual orientation. As a result, addressing social needs helps reduce some of these differences.

While efforts have been made to improve health disparities, closing the gap will require addressing the influence of social determinants and developing solutions aimed at education, income, social and welfare services, affordable housing, job creation, labor market opportunities and transportation.12 Research shows that these efforts can make a difference: one study found that moving low-income residents to newly constructed low-income housing in a middle-class neighborhood correlated with better self-reported health, decreased substance use, increased rates of employment and lower exposure to neighborhood violence.13

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has exacerbated the social determinants of health, particularly for the world’s most vulnerable populations. The impact on global markets has caused mass layoffs, interruptions in income and closed schools. The unprecedented nature of the pandemic has further highlighted the importance of back up childcare, quality and affordable health care, stable housing and widespread availability of healthy and nutritious foods. A Business Group on Health blog explores COVID-19’s impact on the social determinants of health.

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has exacerbated the social determinants of health, particularly for the world’s most vulnerable populations. The impact on global markets has caused mass layoffs, interruptions in income and closed schools. The unprecedented nature of the pandemic has further highlighted the importance of back up childcare, quality and affordable health care, stable housing and widespread availability of healthy and nutritious foods. A Business Group on Health blog explores COVID-19’s impact on the social determinants of health.

Improve Performance

Addressing social needs can reduce absenteeism, increase engagement and positively impact business performance. A 2018 study of over 6,000 employees from four large U.S. manufacturing plants found those living in communities facing social challenges had considerably higher rates of absenteeism and tardiness.* Furthermore, employees reported high levels of stress associated with caregiving, divorce, domestic violence and other external factors, which caused a lack of focus, low morale and, in rare cases, accidents at work.14

Position Company as an Employer of Choice

Today’s employees are looking to businesses, including their own employer, to take the lead on social and environmental change.15 Sixty-four percent of millennials said they wouldn’t even take a job at a company that wasn’t socially responsible, and three-quarters indicated they’d take a pay cut to work for a company that aligned with their values.16

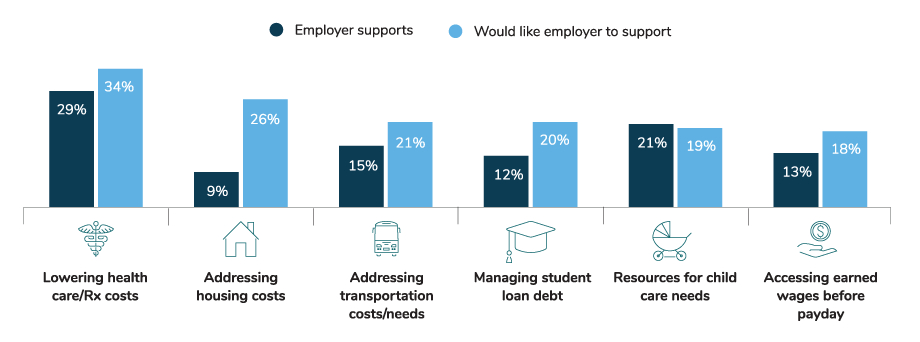

Though many large employers strive to make a social impact that aligns with their brand and customer priorities, few have tapped into the workforce potential of addressing social determinants. Aligning corporate social responsibility with the social needs of your employees, and likewise considering social determinants when designing benefits and well-being initiatives, can help employers build a healthy, competitive and engaged workforce more effectively—and it’s what employees need. Specifically, 34% of employees want assistance in addressing health care/Rx costs, housing (26%), transportation (21%), student loan debt (20%), child care (19%), and access to earned wages before payday (18%).17

* The community health measures used as proxies to identify community health were a high percent of children on free or reduced-price lunch (proxy for economic stability), high rate of drug overdose deaths (proxy for social and community context) and high physical inactivity and adult smoking rates (proxies for health and health behaviors).

- 1 | McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Aff. 2002; 21:78-93.

- 2 | Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it's time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;129 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):19–31.

- 3 | Janphear BP, Kahn RS, Berger O, Auinger P, Bortnick SM, Nahhas RW. Contribution of residential exposures to asthma in U.S. children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2001; 107.

- 4 | Brown P. Race, class, and environmental health: A review and systematization of the literature. Environ Res. 1995; 69:15-30

- 5 | Chuang YC, Cubbin C, Ahn D, Winkleby MA. Effects of neighbourhood socioeconomic status and convenience store concentration on individual level smoking. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005; 59:568-73.

- 6 | Gordon-Larsen P, Nelson MC, Page P, Popkin BM. Inequality in the built environment underlies key health disparities in physical activity and obesity. Pediatrics. 2006; 117:417-24.

- 7 | Kaplan GA, Keil JE. Socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular disease: A review of the literature. Circulation. 1993; 88:1973–98.

- 8 | McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: Links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010; 1186:190–222.

- 9 | Price LH, Kao HT, Burgers DE, Carpenter LL, Tyrka AR. Telomeres and early-life stress: An overview. Biol Psychiatry. 2013; 73:15-23.

- 10 | Kaiser Family Foundation. Disparities in health and health care: Five key questions and answers. https:// www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/disparitiesin-health-and-health-care-five-key-questions-andanswers/. Accessed February 18, 2020.

- 11 | Center for American Progress. How to close the LGBT health disparities gap. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/lgbtq-rights/reports/2009/12/21/7048/ how-to-close-the-lgbt-health-disparities-gap/. Accessed February 15, 2020

- 12 | Singh GK, Daus GP, Allender M, et al. Social determinants of health in the United States: Addressing major health inequality trends for the Nation, 19352016. Int J MCH AIDS. 2017;6(2):139–164.

- 13 | Fautha RC, T L, Brooks-Gunn J. Short-term effects of moving from public housing in poor to middle-class neighborhoods on low-income, minority adults’ outcomes. Social Science & Medicine. 2004; 59:2271-84.

- 14 | McHugh M, French D, Farley D, et al. Community health and employee work performance in the American manufacturing environment. Journal of Community Health. 2019; 44:178–84.

- 15 | Cone Communications. 2017 Cone Communications CSR Study. Available at https://www.conecomm.com/2017-cone-communications-csr-study-pdf. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- 16 | Cone Communications. 2016 Cone Communications Millennial Employee Engagement Study. Available at: http://www.conecomm.com/research-blog/2016-millennial-employee-engagement-study. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- 17 | Optum/Business Group on Health. Well-being and the employee experience. Available at: https://www.optum.com/resources/library/wellness-to-well-being. html. Accessed April 17, 2020

More Topics

Articles & Guides-

IntroductionSocial Determinants: Acting to Achieve Well-being for All

-

Full GuideSocial Determinants: Full Guide

-

Part 1Social Determinants: Why Benefits and Well-being Leaders Should Address Social Determinants

-

Part 2Social Determinants: How Benefits and Well-being Leaders Can Get Started

-

Part 3Social Determinants: Income

-

Part 4Social Determinants: Access to Health Care Services

-

Part 5Social Determinants: Food Access and Insecurity

-

Part 6Social Determinants: Transportation

-

Part 7Social Determinants: Childcare

-

Part 8Social Determinants: Housing Instability

-

Part 9Social Determinants: Racism

This content is for members only. Already a member?

Login

![]()