June 15, 2021

Racism is a social determinant of health that creates and reinforces inequities in health and well-being across the globe. Racism can be expressed consciously, but more frequently, unconsciously, in a manner that’s hidden or can be rationalized through speech, policies, practices and processes that diminish the rights, opportunities and power of racial groups. Racism is persistent in societies around the world, and it has a deep, lasting impact on mental, physical and financial health.

Source: National Public Radio, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Discrimination in America. 2018. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/horp/discrimination-in-america/

Recently, large employers have made strong commitments to end racism and advance equity for employees and their families, as well as in local communities. Benefits and well-being leaders have a role to play in advancing these goals. This includes deepening their understanding of racism and acting to address:

- How experiences with racism—in and outside of the workplace—impact employees’ physical, emotional and financial health;

- How racism shows up in the health care experience; and

- How the design and delivery of health and well-being benefits, policies and practices can mitigate or reinforce racial health disparities.

This section of the Business Group’s Social Determinants: Acting to Achieve Well-being for All Guide provides overviews of the relationship between racism and three core dimensions of well-being—mental health, physical health and financial health—with employer considerations unique to each area. While action is needed at a granular, programmatic level, employers will also need to take a systematic approach to address racism and bias that is embedded in the organization’s culture, policies and benefits. This work will require collaboration and a shared sense of responsibility among health and well-being leaders and other business and HR teams, such as Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI), compensation, talent management and employee resource groups (ERGs). The Business Group has identified the following priority actions for employers as they work to address racism and its impacts on health, with the ultimate goal of achieving health equity, “when every person has the opportunity to ‘attain his or her health potential’ and no one is ‘disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of social positions or other socially determined circumstances”.1

Priority Actions to Advance Racial Equity Across Mental, Physical and Financial Health

- Assess current and prospective benefits to identify racial gaps in accessibility, participation, employee experience, outcomes and cultural consciousness. This assessment should include pinpointing gaps in benefits that would support Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) employees.

- Gain input and feedback from employees about their health and well-being needs, along with changes they would like to see to the benefit portfolio. Partnering with ERGs can be key to these efforts.

Although racism’s impact on health has been well documented, many people still deny its effect, with only 42% of respondents indicating that they believe systemic racism is one of the main reasons people of color have poor health outcomes, approximately 33% disagreeing and nearly 25% choosing “neutral”, according to a 2020 RAND study.

- Require current and future vendor partners to meet equity, diversity and inclusion standards.

- Require cultural competency from those providing health and well-being services for employees and internal leaders. Training should serve as a precursor for accountability.

Additional Resources on Racism and Health and Well-being

With increased awareness of racism and racial inequities, people are seeking ways to learn about racism and what they can do to advance racial justice and equity in their communities and organizations. For health and well-being leaders, this learning journey is both personal and professional. It may be uncomfortable and potentially painful but understanding systemic racism and its history is essential to changing the racial inequities that exist today. An important first step in this process is remembering that many people have not had the privilege of learning about racism and its harmful impact; they have been experiencing racism their entire lives. The following are examples of resources that can be helpful in increasing one’s understanding of race and racism:

- A CEO Blueprint for Racial Equity, a roadmap developed by FSG, PolicyLink and JUST Capital

- Glossary for Understanding the Dismantling Structural Racism/Promoting Racial Equity Analysis, a resource developed by The Aspen Institute

- How to Be an Antiracist, a 2019 nonfiction book by Ibram X. Kendi

- Historical Foundations of Race, an educational website from National Museum of African American History & Culture

- 1619, a podcast by The New York Times

- How Racism Makes Us Sick, a TED Talk by Dr. David R. Williams of Harvard University

Racism and Mental Health

Racism is one of the many factors that can have an effect on mental health risks and outcomes. A recent example of its far-reaching and negative impact is the murder of George Floyd, as anxiety and depression markedly increased among Black and Asian Americans after the video of Floyd’s murder became public.2 According to researchers, including Dr. David Williams, one of the foremost scholars on racism and health, there are several ways that racism impacts mental health, including through experiencing or anticipating racism, as well as the far-reaching effects of structural racism.3 The findings below summarize the seminal work of Dr. Williams and his colleagues, which documents racism’s toll on the mental health of adults and children across the world.

The Impact of Experiencing Racism on Mental Health

Not surprisingly, experiencing and even anticipating racial discrimination can cause negative emotional responses and lead to coping mechanisms or behaviors that can increase the risk of poor health.4,5 It has also been shown that even after adjusting for socioeconomic status, discrimination contributes to racial disparities in mental health.3,6 Discrimination doesn’t need to be overt to have negative effects, as research shows that unconscious bias can also be detrimental to mental health.3

- Experiencing discrimination is associated with poor mental health outcomes, such as anxiety and depression.3 Research from across the globe has documented this relationship. A study in the United Kingdom, for example, found a relationship between the number of experiences of discrimination and mental health.3,7 Other studies show that exposure to discrimination “predicted worse mental health (e.g., anxiety and depression symptoms)” and was “inversely associated with positive mental health (e.g., resilience, self-worth, self-esteem) among children 0-18 years old.” 8, 3

- Experiencing racism indirectly is associated with mental health symptoms. Research shows that secondhand exposure to racism can cause anxiety and depression in children, even if they weren’t exposed to the discrimination themselves.3,9 And according to a large study in the U.K., experiences of discrimination in mothers was associated with social and emotional issues in their children years later. 10

- Anticipating discrimination is associated with worse psychological health. Vigilance, defined as “living in a state of psychological arousal in order to monitor, respond to, and attempt to protect oneself from threats linked to potential experiences of discrimination and other dangers in one’s immediate environment” has found to be associated with a number of mental health effects, including depressive symptoms (a study of Baltimore adults noted that vigilance “contributed to the black-white disparity in depression”), negative emotions and lower psychological health.3,11

Disparities in Mental Health

Rates of mental health disorders are generally similar across races and ethnicities in the U.S. (and are sometimes even lower in minority groups). However, the American Psychiatric Association points out that “lack of cultural understanding by health care providers may contribute to underdiagnosis and/or misdiagnosis of mental illness in people from racially/ethnically diverse populations.”i

When assessing mental health disparities across diverse populations, it’s important to take age and gender into account, as their addition can reveal striking differences that need attention. For example, although racial and ethnic minorities have historically had lower rates of suicide than white people, attention is now being paid to the “crisis of Black youth suicide,” as suicide is the second and third leading cause of death in Black children aged 10-14 and Black adolescents aged 15-19, respectively.ii

It’s also important to bear in mind that the consequences of mental health disorders are not felt equally. For example, “depression in Blacks and Hispanics is likely to be more persistent” (i.e., last over a longer term).i It’s also been cited that minority groups have a higher disability burden from mental health disorders than white people.i

Sources

i|American Psychiatric Association. Mental Health Disparities: Diverse Populations. Accessed April 1, 2021.

ii |National Institute of Mental Health. Addressing the Crisis of Black Youth Suicide. Accessed April 1, 2021.

- Racial bias among health care professionals – whether conscious or unconscious – can impact mental health by influencing care access and quality.3 For example, a study showed that white patients were more likely to get mental health appointments than Black patients.12 Another study conducted over 5 years at a psychiatric emergency room showed that clinicians spent less time evaluating Black patients compared to white patients, and that Black patients were overmedicated compared to others.13

- Internalized racism, the acceptance of negative beliefs by those who are marginalized, has numerous negative effects on mental health and emotional well-being.3 Research from multiple studies shows that internalized racism is associated with higher alcohol consumption, psychological distress, depressive symptoms and lower levels of self-esteem, to name a few.14

A systematic review examining implicit racial and ethnic bias among health care professionals found that “most health care providers appear to have implicit bias in terms of positive attitudes toward [w]hites and negative attitudes toward people of color.” Further, the study authors noted that “implicit bias was significantly related to patient–provider interactions, treatment decisions, treatment adherence, and patient health outcomes.” 15

The Impact of Structural (or Institutional) Racism on Mental Health

Scholars recognize structural racism as “the most important way” that racism impacts health.4 While there isn’t consensus around a singular definition of structural racism, “all definitions make clear that racism is not simply the result of private prejudices held by individuals, but is also produced and reproduced by laws, rules and practices, sanctioned and even implemented by various levels of government, and embedded in the economic system as well as in cultural and societal norms.”16 Forms of structural racism that negatively impact mental health include, but aren’t limited to, racial segregation and police violence.

- Racial residential segregation harms mental health by creating impoverished and disadvantaged communities, thereby increasing exposure to chronic stressors.4 These stressors include experiences like witnessing or experiencing crime, violence and drug use, as well as stressors related to living in substandard housing and not having access to green space or safe playgrounds. For example, research shows that “Black, Latinx, and low-income mothers are disproportionately exposed to gun violence,” and that exposure to community violence has a negative effect on mental health, including higher risk of anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder and depression.17

- Police violence and killings negatively affect mental health. Rates of police violence against people of color are startling in the U.S.: Black, American Indian and Alaska men and women are significantly more likely than their white counterparts to be killed by police; the same is true for Latino men. And among young Black men, a 2019 study found police violence is a leading cause of death.18 Such physical violence causes mental and emotional trauma that extends beyond the victims of violence. For example, just as the murder of George Floyd negatively affected the mental health of Black and Asian Americans, a 2018 study found that police killings of unarmed Black Americans were detrimental to the mental health of Black Americans, but not white Americans.19

Ideas for Action

Eliminating racism in societies across the world is necessary to improving mental health outcomes and disparities. As a part of this effort, benefit and well-being leaders can work to offer anti-racist mental health care to employees and their families. In addition to the Priority Actions to Advance Racial Equity Across Mental, Physical and Financial Well-being, specific recommendations to address racism and mental health include:

- Assessing how current and future vendor partners are providing anti-racist mental health care. This may include adding questions to request for proposals, having regular conversations with vendors (such as creating a standing agenda item during vendor check-ins and summits) and asking vendors for reporting metrics on their efforts.

- Requiring cultural competency training among all mental health professionals, including those that are a part of the health plan, employee assistance program (EAP) and mental health point solutions. This is of particular importance since there are so few non-white mental health professionals in the U.S., and because mental health care is reliant on trust and understanding.

- Increasing diversity among mental health providers. This may include setting benchmark goals for vendor partners to meet year over year.

- Gaining input and feedback from employees on ways to improve mental health care for diverse populations. This can help overcome common assumptions and identify blind spots; for example, after asking for feedback, one company received requests from Indigenous employees to have an Elder included in their network of mental health professionals.

Racism and Physical Health

Just as racism negatively affects mental health, it also impacts physical health, leading to stark racial and ethnic disparities in the incidence, prevalence and outcomes of many health conditions, as well as differences in life expectancy among white and Black Americans. Racism influences physical health through implicit and explicit bias inside and outside of the health care system and structural racism.

Racial Discrimination and Physical Health

Racial discrimination is detrimental to physical health for a myriad of reasons; it can impact the type and quality of care that patients receive, erode patient trust in the health care system (thereby affecting care- seeking behavior and patient’s experience with providers), and be a chronic stressor that damages physical health over time.

- Racial bias among health care professionals can impact the delivery and quality of health care. The often-cited landmark report, Unequal Treatment, published in 2003, found that “racial and ethnic minorities tend to receive a lower quality of healthcare than non-minorities, even when access-related factors, such as patients’ insurance status and income, are controlled” and that “stereotyping, biases, and uncertainty on the part of healthcare providers can all contribute to unequal treatment.”20 A recent systematic review confirms that this problem still exists with health care professionals, showing that they exhibit the same levels of unconscious bias as the broader population. Furthermore, the review pointed to correlational evidence that “biases are likely to influence diagnosis and treatment decisions and levels of care in some circumstances.”21 The pervasive undertreatment of pain in Black patients is just one example of the ways that provider bias degrades health care quality.22 Many medical students and residents “hold beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites, many of which are false and fantastical in nature, and that these false beliefs are related to racial bias in pain perception.”23 Bias also plays a role in the marked maternal health disparities in the U.S., as well as disparities in cardiovascular treatment, to name just a few conditions that racial bias detrimentally impacts.

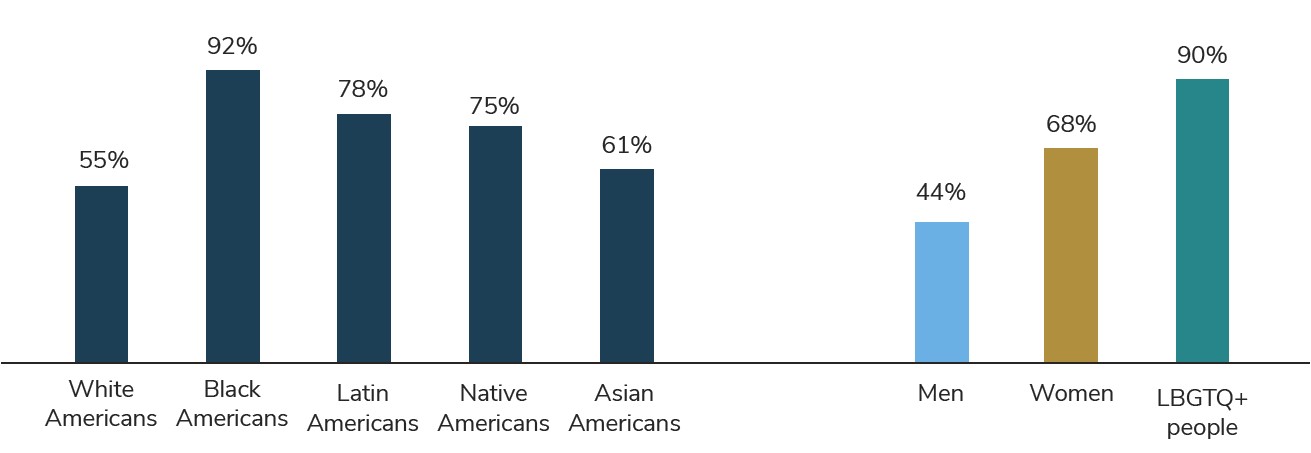

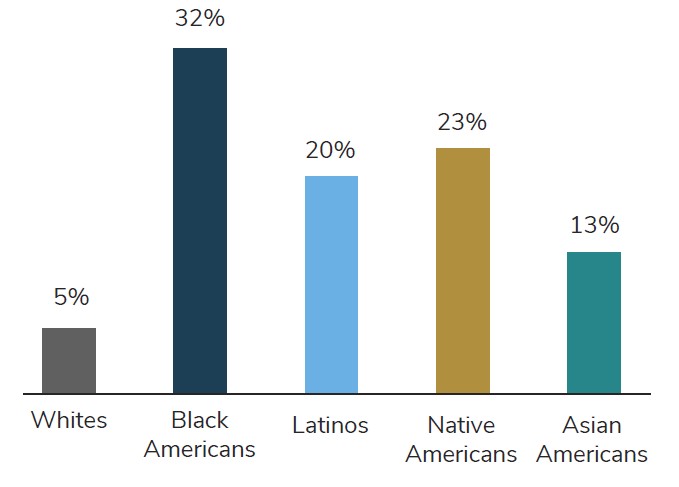

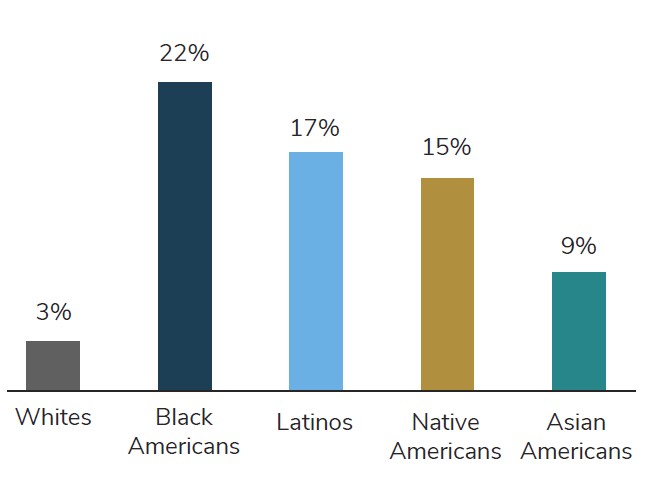

- Current and historical racism can erode patient trust and impact care-seeking behavior. Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) have been exploited, harmed and excluded by the medical field since the founding of the United States, resulting in medical mistrust among many.24 Research also shows that “medical mistrust is not just related to past legacies of mistreatment, but also stems from people’s contemporary experiences of discrimination in health care.”24 Indeed, a 2017 poll of Americans found that racial and ethnic minorities were far more likely than white Americans to say they were discriminated against by a medical provider and that they have avoided seeking medical care for themselves or a family member due to concern that they would experience discrimination.25 Moreover, Black Americans are less likely to trust doctors, local hospitals and the health care system “to do what is right for them and their communities” than white Americans.26 In addition to impacting patient trust and care-seeking behaviors, racism impacts the patient experience. A metanalysis found “those experiencing racism had approximately 2 to 3 times the odds of reporting reduced trust in healthcare systems and professionals, lower satisfaction with health services and perceived quality of care, and compromised communication and relationships with healthcare providers.”27

- Racism is a psychological stressor that can lead to physical “wear and tear.” Exposure to chronic stress can cause a physiological response that increases vulnerability to health risks, a concept referred to as allostatic load.28 Allostatic load, which is measured by biomarkers like cortisol and lipid levels, is associated with perceived racial discrimination and greater racial and social inequalities. Black Americans display higher levels of allostatic load than white Americans.4 Research shows that allostatic load is associated with poorer physical and mental health status and outcomes, including increased risk for cardiovascular disease.4

Source: National Public Radio, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Discrimination in America. 2018. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/horp/discrimination-in-america/

Racial Bias and Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Racial bias can be found in the health care technology used to assist in clinical decision-making.29 For example, researchers found racial bias in a commercial algorithm used to identify patients with complex health needs, resulting in far less Black patients being identified for care management by more than half.31 Assessing algorithms for bias is important to promoting health care equity, as millions of people could be impacted by these tools. For more information on bias in AI, including how it can be rooted out, listen to the Business Group on Health Podcast: Artificial Intelligence in Health Care: Its Perils (Bias) and Potential.

Structural Racism

Scholars recognize structural racism as “the most important way” that racism impacts health.4 Structural racism affects physical health in several ways. One way is through policies and practices that create racial gaps in educational attainment, job opportunities, pay and wealth, all which influence socioeconomic status, and in turn, health. Another way is through racial segregation, which studies show is still persistent across the U.S.31 The effect of racial segregation on health cannot be overstated, as studies show that racial segregation is associated with untold harm, including increased risk of preterm birth and low birthweight, as well as, “later-stage diagnosis, elevated mortality, and lower survival rates for both breast and lung cancers” among Black people.4 In fact, a study from 2018 concluded that “eliminating racial residential segregation and bringing Black socioeconomic status (SES) to White SES levels would eliminate the White-Black survival gap.”32 Some of the ways that structural racism, including racial segregation, impact health, include:

- Influencing socioeconomic status, which is a ‘fundamental’ driver of health. Racial segregation limits access to educational and job opportunities, which in turn leads to racial income inequality, unemployment and concentrated poverty.4

- Creating communities of concentrated poverty with substandard housing, food swamps and deserts, and a lack of access to safe places for physical activity and play. As described in Social Determinants: Acting to Achieve Well-being for All, both food swamps and food deserts are more common in low-income neighborhoods and those with higher concentrations of racial and ethnic minorities. While 24% of zip codes in the U.S. don’t have a supermarket, that number increases to 55% in zip codes where the median income is below $25,000.33 People who are low-income and racial-ethnic minorities are also more likely than high-income, non-minority groups to live near unhealthy food retailers. Substandard housing also poses numerous health risks, from lead poisoning to asthma, and lack of access to green space, parks and playgrounds inhibits physical activity.

- Affecting access to health care, including high-quality care. Black patients in more segregated areas of the U.S. are more likely than white patients to have surgery at low-quality hospitals.34 As another example, in the early months of the COVID-19 vaccine rollout, racial and ethnic disparities in vaccine access were widely reported; one analysis found that most vaccination sites were located in areas with a greater proportion of white residents and another study found that Black people needed to travel farther to vaccination sites than white people.35

- Exposing BIPOC people to sources of pollution. In the U.S., decades of policies and the disenfranchisement of people of color have led to racial and ethnic communities living near sources of waste and pollution, such as power plants, factories, landfills, sewage treatment centers and highways, more than their white counterparts.36 In fact, one report found “race to be more important than socioeconomic status in predicting the location of the nation’s commercial hazardous waste facilities.”36 This exposure leads to serious and avoidable harm. For example, a study conducted over a 10-year period found that people of color were exposed to significantly more air pollution in the form of nitrogen dioxide, a transportation related pollutant, than white people. Furthermore, the study concluded “that if people of color had breathed the lower [nitrogen dioxide] levels experienced by whites in 2010, it would have prevented an estimated 5,000 premature deaths from heart disease among the nonwhite group.”37 Notably, environmental racism extends beyond U.S. borders, with examples of racial and ethnic inequalities in exposure to pollution across the globe.

Ideas for Action

Eliminating racism in societies across the world is necessary for improving physical health outcomes and disparities. As a part of this effort, benefit and well-being leaders can promote equitable health care for employees and their families. In addition to the Priority Actions to Advance Racial Equity Across Mental, Physical and Financial Well-being, specific recommendations to address racism and physical health include:

- Assessing racial and ethnic health and well-being disparities in your employee population, including but not limited to outcomes, engagement and access to care. This should entail conversations with vendor partners about the data they collect (e.g., race/ethnicity and social needs), the disparities and gaps they have identified and how they plan to expand and improve data collection and reporting in the future.

- Asking how current and future vendor partners are working to eliminate racial and ethnic health disparities. This may include adding questions to request for proposals, having regular conversations with vendors (such as creating a standing agenda item during vendor check-ins and summits) and asking vendors for reporting metrics on their efforts.

- Working with health plan and vendor partners to implement cultural competency and anti-bias training among providers in their networks. This is of particular importance since there are so few non-white doctors in the U.S., (in 2018, only 1,500 of the 21,000 students entering medical school were Black) and bias is so prevalent.

- Increasing diversity among health care providers. This may include setting benchmark goals for vendor partners to meet year over year.

- Expanding your health and well-being strategy to meet employees’ social needs, including access to nutritious food, safe and affordable housing and transportation. This is important for addressing the underlying conditions in employees’ communities that impact their health, well-being, productivity and performance.

- Demonstrating your organizational commitment to racial justice and health equity. This can engender trust, promote communication and provide a safe space for honest feedback. For example, Verizon has shown their commitment by developing a Race & Social Justice Action Toolkit.

- Gaining input and feedback from employees on ways to improve physical health care for diverse populations. This can help overcome common assumptions and identify blind spots.

Racial Inequities and Financial Health

Centuries of white privilege and discrimination have made it difficult for Black, Latinx, Indigenous and certain Asian American and Pacific Islander populations to achieve financial security. Today, longstanding and widening racial gaps in job stability, pay and, most critically, wealth, exist across the globe. Wealth provides a safety net for individuals and families in emergency situations, allows for investments in economic mobility (e.g., education, homeownership, business ownership) and is linked with better health.

To ensure employees’ financial security, promote overall health and well-being, and successfully address racism as a social determinant, benefits and well-being leaders need to understand the gaps that exist and pursue solutions to combat their root causes. Here are a few examples of the profound racial disparities—which are entrenched in structural racism—that exist today.

Pay, Underemployment and Job Stability Inequities

Race-based differences in pay, employment and job stability are forms of systemic racism with deep historical roots. The good news is that they are measurable, and therefore fixable. While this is a problem across the globe, the examples below focus in on disparities in the U.S.

- Income: In the fourth quarter of 2019, the median white worker made 28% more than the median Black worker and 35% more than the median Latinx worker.39

- Education: Black workers are less likely to be employed at a level consistent with their education than their white counterparts. For example, 39% of Black college graduates are in an occupation that doesn’t require a bachelor’s degree, compared to 31% of white college graduates.40

- Unemployment: The Black unemployment rate has stayed close to twice the white unemployment rate since 1972, when the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics began collecting data on Black unemployment. 41 Remaining true in 2020, the unemployment rate in the third quarter was: 13.2% for Black Americans, 11.2% for Latinx Americans, 10.6% for Asian Americans and 7.9% for white Americans.39 Also notable, Black workers with college or advanced degrees reach unemployment levels as low as the national average; in comparison, unemployment for white workers with a high school degree is at the national average.42

- Impact on Economic Crises: Despite higher representation among essential jobs during the COVID-19 pandemic, Black and Latinx workers are more likely to lose their jobs than white workers.42 Related, Hispanic (25%) and Black (35%) workers are less likely than white counterparts in similar roles (43%) to report that they can work from home, which provides job stability and mobility opportunities.43 Unfortunately, recovery from economic crises also varies by race. After the 2007/2008 Great Recession, it took more than 10 years for Black and Asian households to return to their pre-recession median incomes.44

Researchers found that as many as 30 million American workers without a four-year college degree have the skills to move into new jobs that pay approximately 70% more than their current jobs. Unfortunately, a common barrier for job and income mobility is having a college degree. Employers require a four-year college degree for 74% of new jobs in America; this excludes approximately two-thirds of workers, with the impact felt most by Black and Latinx workers.45,46

Wealth Inequities

The wealth gap is a result of centuries of racism and inequality, as well as current structural factors, spanning from access to financial products and services to predatory inclusion of education debt. This issue cannot be explained away by individual actions or personal responsibility and will require systemic solutions to address. Here are a few of the disheartening wealth inequities that exist in the U.S. today:

- Overall Wealth: The typical white family’s wealth ($188,200) is approximately 8 times greater than the typical Black family’s wealth ($24,100) and 5 times the typical Hispanic family’s wealth ($36,100).47

- Savings: Black families have fewer liquid assets ($1,500) than white families ($8,100), which becomes particularly important during emergency situations. Beyond the pay and employment disparities described above, less access to affordable financial tools and low-interest loans contribute to this gap. Furthermore, 72% of white families say they could borrow $3,000 from family or friends, compared to 41% of Black families and 58% of Hispanic families.47

- Retirement Savings: Black families (41%) and Hispanic families (35%) are less likely to have retirement savings than white families (68%).48 Therefore, it’s not surprising that the average amount of family retirement savings is significantly more for white families ($157,884) than Black families ($25,212) and Hispanic families ($28,581).49 One reason for this gap is eligibility to participate in employer-sponsored retirement plans, but even with access, there are still disparities: 90% of white families, 80% of Black families and 75% of Hispanic families participate in these plans.41

- Home Ownership: Black families (46%) and Hispanic families (51%) are significantly less likely to own their house than white families (76%).50 Furthermore, Black and Latinx mortgage applicants are charged an average of nearly .08% more in interest and heavier refinance fees than white borrowers. Evidence also suggests that at least 6% of rejected Black and Latinx applications would have been accepted if the applicant were white; when researchers used the income and credit scores of rejected applications but deleted race identifiers, the applications were accepted.51,52 Even once Black and Hispanic homeowners get over these hurdles, they pay a 10%-13% higher tax rate on average than white homeowners within the same local property tax jurisdiction.53

- Debt: While Black families ($8,554) have less debt on average than white families ($32,838), they are the only racial group that owes more than their belongings are worth.54 It’s also notable that Black families are forced to rely on high-interest debt and receive higher fines for loan defaults than white families.55

- Inheritance: White families (30%) are more likely to receive inheritance than Black families (10%) and Hispanic families (7%).41

Myths commonly used to explain the racial wealth gap do not come close to accounting for the vastness of the gap. For example, at comparable income levels, white Americans spend 1.3 times more than Black Americans.56

Ideas for Action

In addition to the recommended Priority Actions to Advance Racial Equity Across Mental, Physical and Financial Well-being, these are employer actions to address racial and ethnic disparities in financial well-being:

- Adopting equitable pay practices, such as not requesting salary history, paying a living wage and conducting regular pay equity audits to identify and correct pay disparities as necessary.

- Adopting inclusive hiring practices, such as not requiring college degrees, broadening sourcing efforts, eliminating hiring bias (e.g., avoid hiring similar people/backgrounds), eliminating criminal-history questions, and ensuring that people of the global majority are not hired into lower-level positions than white people with similar experience.

- Promoting liquid asset building through automatic savings features, employer-sponsored emergency savings plans and emergency savings sidecar accounts (even better with an employer match).

- Providing access to earned wages before payday and/or paying wages weekly instead of biweekly.

- Offering an emergency relief fund and/or no- or low-interest loans.

- Providing student loan repayment and other educational assistance, such as tuition assistance and scholarships for employees or dependents.

- Offering a down payment assistance program and/or other supports for housing instability.

- Expanding access to retirement accounts (with auto-enrollment and contribution matches), FSAs, leave benefits and other cost-saving benefits.

- Tracking and reporting on participation in financial well-being benefits by race and ethnicity.

For more general practices related to supporting financial well-being and income as social determinants, review the Business Group’s Strategies to Support Financial Well-being Guide and Social Determinants: Income.

- 1 | U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health equity. March 11, 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/healthequity/index.htm. Accessed Tuesday, May 17, 2020.

- 2 | Fowers A and Wan W. Depression and anxiety spiked among black Americans after George Floyd’s death. The Washington Post. June 12, 2020. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/06/12/mental-health-george-floyd-census/?arc404=true. Accessed March 2, 2021.

- 3 | Williams D. Stress and the mental health of populations of color: Advancing our understanding of race-related stressors. J Health Soc Behav. 2018;59(4)

- 4 | Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: Evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:105-125.

- 5 | Gibbons FX, Stock ML. 2017. Perceived racial discrimination and health behavior: Mediation and moderation: Oxford University Press

- 6 | Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Williams S, Mohammed SA, Moomal H, Stein DJ. Perceived discrimination, race and health in South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2008; 67(3):441-52.

- 7 | Wallace S, Nazroo J, Bécares L. Cumulative effect of racial discrimination on the mental health of ethnic minorities in the United Kingdom.” Am J Public Health. 2016;106(7):1294–300.

- 8 | Priest N, Paradies Y, Trenerry B, Truong M, Karlsen S, Kelly Y. A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people.” Social Science & Medicine. 2013;95:115–27.

- 9 | Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Wills TA, Brody G. Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: A panel study. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004; 86(4):517-29.

- 10 | Becares L, Nazroo J, Kelly Y. A longitudinal examination of maternal, family, and area-level experiences of racism on children’s socioemotional development: Patterns and possible explanations. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;142:128–35.

- 11 | LaVeist TA, Thorpe RJ Jr, Pierre G, Mance GA, Williams DR. The relationship among vigilant coping style, race, and depression. J Soc Issues. 2014; 70(2):241-255.

- 12 | Kugelmass H. “Sorry, I’m not accepting new patients”: An audit study of access to mental health care. J Health Soc Behav. 2016;57(2):168-83.

- 13 | Segal SP, Bola JR, Watson MA. Race, quality of care, and antipsychotic prescribing practices in psychiatric emergency services. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(3):282-6.

- 14 | Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009 Feb; 32(1):20-47.

- 15 | Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias Among Health Care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: A systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):e60-e76.

- 16 | Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How structural racism works — racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities. NEJM. 2021; 384:768-773.

- 17 | Leibbrand C, Rivara F, Rowhani-Rahbar A. Gun violence exposure and experiences of depression among mothers. Prev Sci. 2021;1-11.

- 18 | Edwards F, Lee H, Esposito M. Risk of being killed by police use of force in the United States by age, race–ethnicity, and sex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2019;116(34): 16793-16798.

- 19 | Edwards F, Lee H, Esposito M. Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans: A population-based, quasi-experimental study. The Lancet. 2018;319(10144):302-310.

- 20 | Institute of Medicine. 2003. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- 21 | FitzGerald, C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18.

- 22 | Meghani SH, Byun E, Gallagher RM. Time to take stock: A meta-analysis and systematic review of analgesic treatment disparities for pain in the United States. Pain Med. 2012;13(2):150-74.

- 23 | Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Jordan R. Axt, M. Oliver N. Racial bias in pain assessment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2016;113(16): 4296-4301.

- 24 | The Commonwealth Fund. Understanding and Ameliorating Medical Mistrust Among Black Americans. January 14, 2021. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/2021/jan/medical-mistrust-among-black-americans Accessed May 26, 2021.

- 25 | Blendon RJ, Casey LS. Discrimination in the United States: Perspectives for the future. Health Services Research. 2019;54(S2): 1467-1471

- 26 | Hamel L, Lopes L, Munana C, Artiga S, Brodie M. The undefeated survey on race and health. KFF. October 13, 2020. Available at: https://www.kff.org/report-section/kff-the-undefeated-survey-on-race-and-health-main-findings/. Accessed May 26, 2021.

- 27 | Cormack BJ, Harris D, Paradies RY. Racism and health service utilisation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0189900.

- 28 | Guidi J, Lucente M, Sonino N, Fava G A.: Allostatic load and its impact on health: A systematic review. Psychother Psychosom. 2021;90:11-27.

- 29 | Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. 2019;366(6464):447-453.

- 30 | Gee GC, Ford CL. Structural racism and health inequities: Old issues, new directions. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8(1):115-132.

- 31 | Williams A, Emamjomeh A. America is more diverse than ever — but still segregated. The Washington Post. Updated May 10, 2018. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2018/national/segregation-us-cities/. Accessed May 10, 2021

- 32 | Popescu I, Duffy E, Mendelsohn J, Escarce JJ. Racial residential segregation, socioeconomic disparities, and the White-Black survival gap. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0193222.

- 33 | National Bureau of Economic Research. Food deserts and the causes of nutritional inequality. 2018. Available at: https://www.nber.org/papers/w24094.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2020.

- 34 | Dimick J, Ruhter J, Sarrazin MV, Birkmeyer JD. Black patients more likely than whites to undergo surgery at low-quality hospitals in segregated regions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013 Jun;32(6):1046-53.

- 35 | McMinn S, Chatlani S, Lopez A, Whitehead S, Talbot R, Fast A. Across the South, COVID-19 vaccine sites missing from Black and Hispanic neighborhoods. NPR. February 5, 2021. Available at: https://www.npr.org/2021/02/05/962946721/across-the-south-covid-19-vaccine-sites-missing-from-black-and-hispanic-neighbor. Accessed May 26, 2021.

- 36 | Beech P. What is environmental racism? World Economic Forum. July 31, 2020. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/07/what-is-environmental-racism-pollution-covid-systemic/. Accessed May 10, 2021.

- 37 | Langston J. People of color exposed to more pollution from cars, trucks, power plants during 10-year period. UW News. September 14, 2017. Available at: https://www.washington.edu/news/2017/09/14/people-of-color-exposed-to-more-pollution-from-cars-trucks-power-plants-during-10-year-period/. Accessed May 10, 2021.

- 38 | Boen C, Keister L, Aronson B. Beyond net worth: Racial differences in wealth portfolios and Black-White health inequality across the life course. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2020;61(2):153-169.

- 39 | Inequality.org. Racial economic inequality. 2020. Available at: https://inequality.org/facts/racial-inequality/#racial-wealth-divide. Accessed December 3, 2020.

- 40 | U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor force statistics from the current population survey. 2021. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/web/empsit/cpsee_e16.htm. Accessed December 3, 2020.

- 41 | Ajilore O. On the persistence of the Black-White unemployment gap. Center for American Progress. February 24, 2020. Available at: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2020/02/24/480743/persistence-black-white-unemployment-gap. Accessed December 3, 2020.

- 42 | Williams J, Wilson V. Black workers endure persistent racial disparities in employment outcomes. Economic Policy Institute. August 27, 2019. Available at: https://www.epi.org/publication/labor-day-2019-racial-disparities-in-employment/. Accessed December 5, 2020.

- 43 | Karpman M, Zuckerman S, Gonzalez D, Kenney, GM. The COVID-19 pandemic is straining families’ abilities to afford basic needs. Urban Institute. April 2020. Available at: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/102124/the-covid-19-pandemic-is-straining-families-abilities-to-afford-basic-needs_5.pdf. Accessed December 4, 2020.

- 44 | Wilson V. 10 years after the start of the Great Recession, Black and Asian households have yet to recover lost income. Economic Policy Institute September 12, 2019. Available at: https://www.epi.org/blog/10-years-after-the-start-of-the-great-recession-black-and-asian-households-have-yet-to-recover-lost-income/. Accessed December 4, 2020.

- 45 | Blair PQ, Castagnino TG, Groshen, EL, et al. Searching for stars: Work experience as a job market signal for workers without bachelor’s degrees. National Bureau of Economic Research March 2020. Available at: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w26844/w26844.pdf. Accessed December 3, 2020.

- 46 | Opportunity@Work. Navigating with the STARs: Reimaging equitable pathways to mobility. November 2020. Available at: https://opportunityatwork.org/navigating-stars-report/. Accessed December 5, 2020.

- 47 | Bhutta N, Chang AC, Dettling LJ, Hsu JW. Disparities in wealth by race and ethnicity in the 2019 survey of consumer finances. FEDS Notes. September 28, 2020. Available at: https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/disparities-in-wealth-by-race-and-ethnicity-in-the-2019-survey-of-consumer-finances-20200928.htm. Accessed November 16, 2020.

- 48 | Morrissey M. The state of American retirement savings. Economic Policy Institute. December 10, 2019. Available at: https://www.epi.org/publication/the-state-of-american-retirement-savings/. Accessed November 16, 2020.

- 49 | Urban Institute. Nine charts of wealth inequality in America (Updated). October 5, 2017. Available at: https://apps.urban.org/features/wealth-inequality-charts/. Accessed November 10, 2020.

- 50 | U.S. Census. Quarterly residential vacancies and homeownership, fourth quarter 2020. February 2, 2021. Available at: https://www.census.gov/housing/hvs/files/currenthvspress.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- 51 | Brooks KJ. Disparity in home lending costs minorities millions, researchers find. CBS News/Money Watch. November 15, 2019. Available at: 52 | Barlett R, Morse A, Stanton R, Wallace N. Consumer-lending discrimination in the fintech era. National Bureau of Economic Research. June 2019. Available at: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w25943/w25943.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- 53 | Avenancio-Leon CF. Misvaluations in local property tax assessments cause the tax burden to fall more heavily on Black, Latinx homeowners. Washington Center for Equitable Growth. June 10, 2020. Available at: https://equitablegrowth.org/misvaluations-in-local-property-tax-assessments-cause-the-tax-burden-to-fall-more-heavily-on-black-latinx-homeowners. Accessed November 17, 2020.

- 54 | Weller C. Families still downing in consumer debt, adding to financial insecurity. Forbes. January 18, 2020. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/christianweller/2020/01/18/families-still-drowning-in-consumer-debt-adding-to-financial-insecurity/?sh=337e055f7c5b. Accessed November 17, 2020.

- 55 | Blackwell AG, McAfee M. Banks should face history and pay reparations. The New York Times. June 26, 2020. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/26/opinion/sunday/banks-reparations-racism-inequality.html. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- 56 | Darity W, Hamilton D, Paul M, Aja A, Price A, Moore A, et al. What we get wrong about closing the racial wealth gap. Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity. April 2018. Available at: https://socialequity.duke.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/what-we-get-wrong.pdf.

More Topics

Articles & Guides-

IntroductionSocial Determinants: Acting to Achieve Well-being for All

-

Full GuideSocial Determinants: Full Guide

-

Part 1Social Determinants: Why Benefits and Well-being Leaders Should Address Social Determinants

-

Part 2Social Determinants: How Benefits and Well-being Leaders Can Get Started

-

Part 3Social Determinants: Income

-

Part 4Social Determinants: Access to Health Care Services

-

Part 5Social Determinants: Food Access and Insecurity

-

Part 6Social Determinants: Transportation

-

Part 7Social Determinants: Childcare

-

Part 8Social Determinants: Housing Instability

-

Part 9Social Determinants: Racism

This content is for members only. Already a member?

Login

![]()