The degree of reluctance many have toward receiving COVID-19 vaccines is well documented, with only 56% of respondents from a nationally representative December 2020 JAMA survey reporting they would likely get vaccinated.1 Contributing to this problem is the history of systemic racism and its consequences, which have eroded both trust in vaccines and the health care system at large for Black and Hispanic communities. More respondents from both groups reported a “wait and see” approach to getting vaccinated compared to White adults.2 Early data suggest that while these communities are receiving vaccine doses, ensuring that they are actually administered to people living there (rather than to non-residents visiting the sites to receive them) remains a challenge.

Equitable vaccine distribution is essential to combatting hesitancy and increasing overall enthusiasm for receiving COVID-19 vaccines. According to a recent Kaiser Family Foundation survey, approximately 52% of Black adults reported they are “not too” or “not at all” confident that the vaccine distribution efforts are taking into account the needs of Black people, with only about 58% of Black adults saying they are confident that the COVID-19 vaccines in the U.S. are being distributed fairly.3

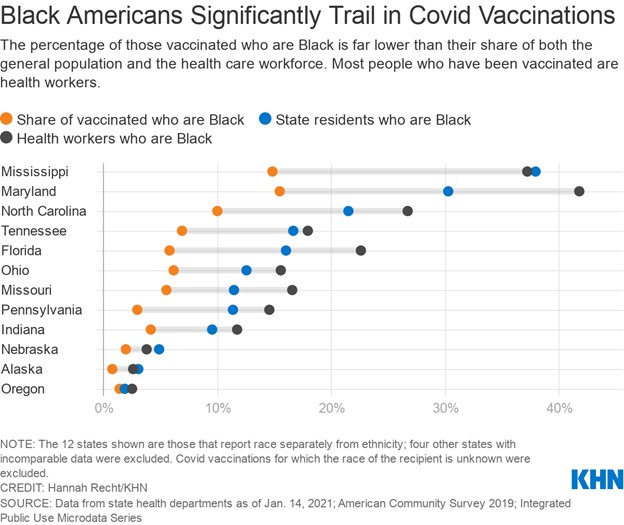

This concern is not unfounded: Across the 23 states reporting vaccination data by race/ethnicity, there was a consistent pattern of Black and Hispanic people receiving smaller shares of vaccinations compared to their share of cases and deaths and to their share of the total population.4 Similarly, those living in rural communities are more likely to report that they definitely will not get a COVID-19 vaccine or would only do so if required.

As large employers consider establishing their own vaccination sites, there are several factors to keep in mind:

- Location matters: COVID-19 has hit communities of color the hardest, along with those of lower socioeconomic status. When setting up a vaccine site, consider using locations in geographic proximity to these communities, as well as those that are accessible by multiple modes of transportation. Disseminating information in multiple languages also promotes access for immigrant and/or other multilingual communities.

- Use targeted, transparent communications: Messaging may resonate differently according to individuals’ most pressing priorities. For example, lower-income families and/or employees not on the company’s medical plan may view perceived out-of-pocket costs for the vaccine as a barrier to receiving it. Consider leveraging internal survey data or external sources to learn which employee cohorts are choosing not to take the vaccine and then acting on that information accordingly.

- Direct employees to reputable information sources: The majority of those who have not yet gotten vaccinated (94% of all adults) say they do not have enough information about when people like them will be able to get the vaccine (60%) and where they should go to get it (55%).3 Therefore, it is important to ensure that any communications include up-to-date information/data from federal, state and/or county authorities. Consider housing all resources related to COVID-19 in one centralized location, including any internally developed materials as well as links to credible external sources. This approach will ensure that all information related to coverage and availability can be accessed easily.

- Leverage trusted messengers: While demonstrated efficacy is important to convincing the public to get the vaccine, many will also rely on the counsel of trusted advisors. Kaiser Family Foundation reports that the top three trusted stakeholders for those deciding whether to get vaccinated include 1) doctors and other health care providers; 2) the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); and 3) state/local public health departments. Consider featuring medical providers (to the extent possible), trusted community members and employee resource group (ERG) leaders in communication campaigns.

References

- 1 | Szilagyi PG, Thomas K, Shah M. et al. National Trends in the US Public’s Likelihood of Getting a COVID-19 Vaccine—April 1 to December 8, 2020. December 29, 2020. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2774711. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 2 | Kaiser Family Foundation. Vaccine Monitor: Nearly Half of the Public Wants to Get a COVID-19 Vaccine as Soon as They Can or Has Already Been Vaccinated, Up across Racial and Ethnic Groups Since December. January 27, 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/press-release/vaccine-monitor-nearly-half-of-the-public-wants-to-get-covid-19-vaccine-as-soon-as-they-can-or-has-already-been-vaccinated-up-across-racial-and-ethnic-groups-since-december/. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 3 | Hamel L, Kirzinger A, Lopes L et al. Vaccine Distribution. KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: January 2021. January 22, 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/report/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor- january-2021/. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 4 | Ndugga N, Pham O, Hill L et al. Latest Data on COVID-19 Vaccinations Race/Ethnicity. KFF. February 2, 2021. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/latest-data-covid-19-vaccinations-cases-deaths-race-ethnicity/. Accessed February 10, 2021.