April 14, 2021

In the United States, adults and babies die from preventable causes during pregnancy, childbirth and soon after delivery significantly more than in other wealthy countries.1 While maternal mortality rates are decreasing globally, they are rising the United States.2 Moreover, appalling racial and ethnic disparities exist that cannot be explained away by income or education and must be confronted by addressing systemic racism and driving change in the health care system.

This article describes disparities in maternal (or carrier) mortality, why they exist and what employers can do to be part of the solution.

Disparities in Pregnancy-related Deaths

BIPOC people and their babies are at a higher risk for mortality than White people and the babies born to them. In 2019, the maternal mortality rate for Black people was 3.5 times more likely than for White people and 2.5 more likely for Hispanic people. 3

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Tragically, this has been a long-standing problem. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System, Black, American Indian and Alaska Native people were two to three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than White people from 2007-2016.4 For American Indian and Alaska Native people, these disparities increased with age. For example, a 25-year-old American Indian person was nearly three times as likely to die from pregnancy-related causes as a White person the same age; at age 35, that number jumped to over five times as likely. Similarly, a 20-year-old Black person was nearly three times as likely to die from pregnancy-related causes as a White person of the same age, while a 30-year-old Black person was over four times as likely.3

In the U.S., cardiovascular conditions, hemorrhage and infection are the leading causes for maternal mortality, but racial and ethnic differences exist. Also notable, for every maternal death, 70 severe morbidity events are considered near misses.5 Moreover, causes of death after leaving the hospital, such as those related to mental illness, accidents and domestic violence, are often overlooked.6

|

American Indian/Alaska Native |

Asian/Pacific Islander |

Black |

Hispanic |

White |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: U.S. Government Accountability Office

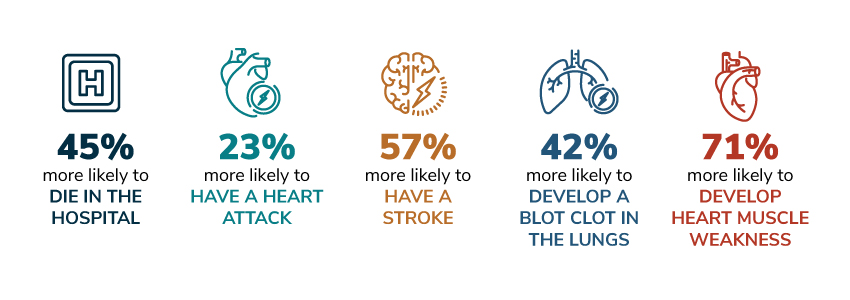

Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal mortality exist regardless of socioeconomic factors. For example, according to the American Heart Association, even after controlling for socioeconomic status, health care access and other medical conditions, Black pregnant women are:

Pregnancy and Birth Experiences Among Trans and Nonbinary People

While recently there’s been a greater emphasis on providing inclusive, gender-affirming medical care, significant knowledge gaps exist regarding pregnancy and birth experiences, including mortality rates, for trans and nonbinary people. This is due in part to the fact that medical systems often limit and/or track gender as male or female. A 2020 review of currently available research found transgender men face substantial obstacles and discrimination from prepregnancy through childbirth.7 To learn more about pregnancy and childbirth among trans and non-binary populations, review relevant resources curated by the Trans Pregnancy Project.

Why Maternal Mortality Disparities Exist in the U.S.

There are many interconnected reasons—deeply engrained in society and the health care system—why health disparities exist today. These issues must be eliminated to save lives.

Provider Bias, Mistreatment and Weathering

- BIPOC people experience weathering, defined as premature aging and increased vulnerability to health risks due to the constant stress of racism. This makes pregnancy riskier for BIPOC people at an earlier age. Experiencing racism and prenatal stress are linked to adverse birth outcomes, such as low birthweight and preterm delivery.8

- Approximately a third of Black people report being racially discriminated against when going to a doctor or health clinic.9 As a result, pregnant Black people may decide not to seek needed care.

- During pregnancy, Black, Hispanic and Indigenous people report significantly higher rates of provider mistreatment, such as shouting, scolding, or being ignored.10

- Failures to believe concerns raised by BIPOC people about their bodies and pain contribute to suboptimal care and maternal mortality. Some White providers still believe myths that Black people experience less pain than White people.11 Since Black patients are 40% less likely to receive medication for acute pain compared to White patients, it’s not surprising that Black patients report being refused a test, treatment or pain medication more than White patients. 12,4

- Because early symptoms are not heard or responded to appropriately, Black people are more likely to experience life-threatening complications during pregnancy. For example, Black women experience signs of preeclampsia (a condition of high blood pressure and unusual protein in urine that can cause dangerous complications) earlier in pregnancy than White women.13,14 Another example is mitral valve stenosis, a form of heart disease that reduces blood flow and can be fatal. Black people are not more susceptible to this rare heart condition; however, “[if left untreated] in pregnancy, mitral stenosis becomes a trap, a really bad death trap,” according to Elizabeth Ofili, MD, MPH, Professor of Medicine at Morehouse School of Medicine and Cardiologist with Morehouse HealthCare.15

- When Black physicians care for Black babies, infant mortality is significantly less.16 Additionally, when patients have physicians that look like them, quality of care, satisfaction, and trust improve.17

Hear Her Campaign

The CDC Hear Her Campaign aims to improve communication between patients and providers by raising awareness of life-threatening warning signs during and after pregnancy. The campaign asserts that “women know their own bodies better than anyone and can often tell when something does not feel right. The campaign seeks to encourage partners, friends, family, coworkers and providers—anyone who supports pregnant and postpartum women—to really listen when she tells you something doesn’t feel right. Acting quickly could help save her life.”

Lack of High-Quality, Affordable Care

- BIPOC people have less access to quality care from contraception to postpartum. Also notable, Black people receive lower-quality care, even when they have the same insurance.18

- BIPOC employees in the U.S. have less access to employer-sponsored health care coverage and programs, as they are overrepresented in non-exempt, hourly positions that are often not eligible for benefits.

- BIPOC employees also have less access to maternity programs, incentives and chronic condition management programs (e.g., addressing heart disease, diabetes), which are often dependent on being benefit-eligible.

- Pregnant people and those planning to be pregnant may not realize their unique needs during pregnancy or be aware of availability of prenatal care.

- People who give birth in hospitals that predominantly serve Black populations have higher rates of maternal complications and worse birth outcomes, such as non-elective C-sections, elective deliveries and maternal mortality.19 Seventy-five percent of Black women deliver babies at predominantly Black-serving hospitals.20

- Unnecessary C-sections are dangerous for birth parents, with high rates of hemorrhage, transfusions, infections and blood clots.21 Moreover, BIPOC patient experience bias, which leads to having symptoms treated less seriously and with less urgency.

- High out-of-pocket costs can be a barrier to ensuring that the best treatment options are taken.

- BIPOC employees have less access to paid sick, parental, family and medical leaves.

People in rural areas experience higher rates of maternal mortality and morbidity than their urban peers. Between 2007 and 2015, over 4,000 rural women would not have experienced maternal morbidity and mortality if they lived in urban areas.23

Employer Actions to Address Disparities and Save Lives

Addressing disparities in maternal mortality requires action from all stakeholders in the health care system, including employers. Large employers can drive change for employees and their families, as well as advance health equity more broadly across the U.S. and globally. Beyond eliminating disparities, employers should strive to ensure that their employees have a positive childbirth experience. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines this as “one that fulfills or exceeds a woman’s prior personal and sociocultural beliefs and expectations, including birth to a healthy baby in a clinically and psychologically safe environment with continuity of practical and emotional support from a birth companion(s) and kind, technically competent clinical staff.”24

Affordable, High-Quality Care and Benefits from Preconception to Postpartum

- Provide access to and encourage preconception counseling to identify risk factors and early interventions. Preconception counseling can reduce maternal and infant morbidity and mortality. 25

- Provide affordable access to certified midwives and doulas. WHO recommends midwives as an evidence-based approach to maternal mortality, and midwives improve psychosocial well-being outcomes for birth parents.16,27

- Provide coverage for birthing centers and access to fertility and maternity Centers of Excellence (COE). COEs should be evaluated for features like data collection, patient outcomes, physician performance, cultural competence, relevant condition management and drills for serious maternal adverse events.

- Pursue value-based pay arrangements for maternity care that promote care quality and deploy appropriate value measures, including C-section reduction and elimination of early elective deliveries.

- Provide education on shared decision-making as it relates to C-sections to reduce elective C-section rates.

- Expand access to telehealth care, maternity programs and innovative solutions that support employees along their parenthood journey. Even better, make these benefits available to employees who are not typically benefit eligible (e.g., hourly, non-exempt). Telehealth options can drive better patient engagement and outcomes. For example, one study found that the introduction of text-based monitoring postpartum (vs. office-based care) led to a 50% reduction in racial disparities of blood pressure ascertainment. 28

- Provide benefits that address transportation barriers.

- Provide access to and encourage participation in centering pregnancy programs that bring together groups of people to make informed, healthy choices related to pregnancy and childbirth.

- Provide employees with paid sick, parental, family and medical leaves.

- Tier premiums, account contributions and/or deductibles based on salary.

- Incentivize engagement in programs and benefits that aim to reduce maternal risks and mortality.

Culturally Competent Care

- Require a diverse, culturally competent network of health care providers from health plans and vendors.

- Work with carriers to implement maternity mortality and complication review boards.

- Explore options for maternity COEs, especially those supporting high-risk pregnancies and located in a way that improves access for marginalized populations.

- Provide a means for employees to find and choose providers who match their race and ethnicity.

- Influence networks to incorporate race and ethnicity in regular trainings and drills, rather than only separate equity, diversity and inclusion trainings.

- Require the use of clinical guidelines, standardized care and checklists to remove harmful individual discretion and implicit bias.

- Require the collection of quality metrics for maternal care and the evaluation of disparities in treatments and outcomes.

Employee Engagement and Supportive Workplaces

- Encourage employees get appropriate preventive screenings and care from preconception through postpartum. Communication campaigns that are appropriately tailored for different populations with vendors, health plans and employee resource groups (ERGs) can be an effective strategy.

- Ensure that employees have access to and are aware of benefits and resources to support their mental health and reduce maternal stress.

- Establish a means, either internally or through a vendor, to listen to pregnant people’s experiences during pregnancy and childbirth, assist with individual cases as needed, and identify systemic issues for intervention.

- Partner with ERGs to ensure BIPOC and LQBTQ+ people understand disparities in maternal health and the supports available to them.

- Ensure that pregnant people have the accommodations and protections they need to be safe at work.

- Commit to and ensure an anti-racist organizational culture and business practices that are established to promote equity, diversity and inclusion and prevent weathering.

Community Health Partnerships and Advocacy

- Support community outreach programs, including faith-based partnerships, that provide BIPOC and LGBTQ+ community members with health outreach and build trust with providers.

- Drive change through partnerships and funding initiatives that improve maternal health. Merck for Mothers is a strong example of a corporate initiative to strengthen maternity care across the globe. Making the connection between community health and their own workforce, the program involves more than 700 Merck employees who serve as Merck for Mothers ambassadors. Ambassadors assemble postnatal supply kits for expectant mothers, collect “hope phones” to equip maternal care sites with needed mobile health tech, and educate employees about maternal health.

- Support legislative efforts, such as the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act, that aim to address maternal health disparities. For example, Blue Cross Blue Shield Association has expressed support for the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act.

More Topics

Articles & Guides- 1 | Tanne JH. US lags other rich nations in maternal health care. BMJ. 2020;371. Available at: https://www.bmj.com/content/371/bmj.m4546.full.

- 2 | Cox KS. Global maternal mortality rate declines—Except in America. Nursing Outlook. 2018. 201;66(5):428-429.

- 3 | Hoyert, DL. Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2019. CDC. April 2021. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality-2021/E-Stat-Maternal-Mortality-Rates-H.pdf.

- 4 | Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, Cox, S, Syverson, C, Seed, K, et al. Racial/Ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related deaths — United States, 2007–2016. September 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6835a3.htm?s_cid=mm6835a3_w.

- 5 | Melillo G. Racial disparities persist in maternal morbidity, mortality and infant health. June 13, 2020. Available at: https://www.ajmc.com/view/racial-disparities-persist-in-maternal-morbidity-mortality-and-infant-health.

- 6 | Levin-Scherz, J. Call to action: Employers should demand higher quality maternity care. Presentation at: Business Group on Health Cost & Delivery Institute Meeting; January 2020. Washington, DC.

- 7 | Besse M, Lampe NM, Mann ES. Experiences with achieving pregnancy and giving birth among transgender men: A narrative literature review. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 2020;93(4):517-528.

- 8 | Nuru-Jeter A, Dominguez TP, Hammond WP, Leu J, Skaff M, Egerter S, et al. “It's the skin you're in”: African American women talk about their experiences of racism: An exploratory study to develop measures of racism for birth outcome studies. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2018. 13(1), 29-39.

- 9 | National Public Radio. Discrimination in America: Experiences and view of African Americans. October 2017. Available at: https://legacy.npr.org/assets/img/2017/10/23/discriminationpoll-african-americans.pdf.

- 10 | Vedam S, Stoll K, Taiwo TK, Rubashkin N, Cheyney M, Strauss N, et al. The giving voice to mothers study: Inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reproductive Health. 2019. 16(77). Available at: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-019-0729-2.

- 11 | Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, and the Tara Hansen Foundation. Stop. look. listen! Highlights from to have and to hold: Maternal safety and the delivery of safe patient care. 2013. Available at: https://www.rwjms.rutgers.edu/RURWJ_SSLAnmatedPDF_FIN/document.pdf.

- 12 | Lee P, Le Saux M, Siegel R, Goyal M, Chen C, Ma Y, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the management of acute pain in US emergency departments: Meta-analysis and systematic review. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2009. 37(9), 1770-1777.

- 13 | Harvard Health Publishing. Preeclampsia and eclampsia. October 2018. Available at: https://www.health.harvard.edu/a_to_z/preeclampsia-and-eclampsia-a-to-z.

- 14 | Shahul S, Tung A, Minhaj M, Nizamuddin J, Wenger J, Mahmood E, et al. Racial disparities in comorbidities, complications, and maternal and fetal outcomes in women with preeclampsia/eclampsia. Hypertens Pregnancy. 34(4), 506-515.

- 15 | Williams, NE. The crucial role of heart health in Black maternal mortality. March 2021. Available at: https://www.self.com/story/heart-health-black-maternal-mortality.

- 16 | Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, Sojourner A. Physician–patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Available at: https://www.pnas.org/content/117/35/21194.

- 17 | Terlizzi EP, Connor EM, Zelaya CE, Ji AM, Bakos AD. Reported importance and access to health care providers who understand or share cultural characteristics with their patients among adults, by race and ethnicity. National Health Stat Report. 2019. 130, 1–12.

- 18 | Gavin NI, Adams KE, Hartmann K, Benedict BM, Chireau M. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of pregnancy-related health care among medicaid pregnant women. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2004. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15499869/.

- Creanga AA, Bateman BT, Mhyre JM, Kuklina E, Shilkrut A, Callaghan, WM. Performance of racial and ethnic minority-serving hospitals on delivery-related indicators. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2014. 211(6), 647-e1.

- 20 | Howell EA, Egorova N, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Black-white differences in severe maternal morbidity and site of care. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2016. 214(1), 122-e1.

- 21 | Teleki, S. Birthing a movement to reduce unnecessary C-sections: An update from California. October 2017. Health Affairs. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20171031.709216/full/.

- 22 | U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to and use of paid family and medical leave: Evidence from four nationally representative datasets. January 2019. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2019/article/racial-and-ethnic-disparities-in-access-to-and-use-of-paid-family-and-medical-leave.htm.

- 23 | Kozhimannil KB, Interrante JD, Henning-Smith C, Admon LK. Rural-urban differences in severe maternal morbidity and mortality in the US, 2007-2015. Health Affairs. December 2019. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00805.

- 24 | World Health Organization. WHO recommendations intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. 2018. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/260178/9789241550215-eng.pdf.

- 25 | Fowler, JR, Mahdy H, Jack BW. Preconception counseling. 2020. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441880/.

- 26 | United Nations Population Fund. The state of world’s midwifery 2014: A universal pathway. A woman’s right to health. 2014. Available at: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/EN_SoWMy2014_complete.pdf.

- 27 | Renfrew MJ, McFadden A, Bastos MH, Campbell J, Channon AA, Cheung NF, et al. Midwifery and quality care: findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care. 2014;20(384):1129-1145.

- 28 | Hirshberg A, Sammel MD, Srinivas SK. Text message remote monitoring reduced racial disparities in postpartum blood pressure ascertainment. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019 Sep;221(3):283-285.