November 29, 2022

Note: This resource is intended to be useful both as a standalone document, as well as the first part of Business Group on Health’s Value-Based Purchasing Guide. Click the link to access additional parts related to other elements of employer value-based purchasing strategy.

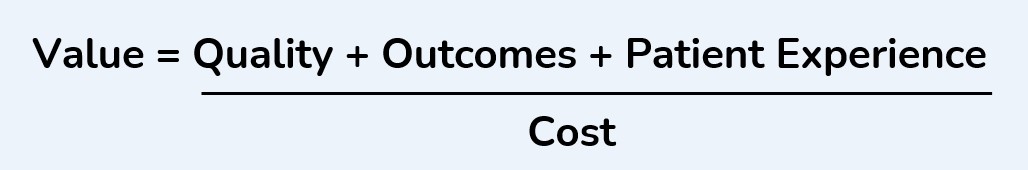

Aligning health care purchasing strategy so that it reimburses providers based on the value of the care that they provide, rather than the volume of that care, requires a shared definition of “value” itself. The Business Group proposes the model below as a good way to think about value in health care purchasing.

Conceptually, the value of a health care service or group of services increases as the quality, level of outcomes and patient experience improve, and the converse is true of the cost. However, each variable in the numerator can be complex to define and measure, and even cost measurements are not always straightforward.

As employers consider various value-based purchasing strategies, they will need to keep these elements of value in mind. Value-based purchasing can come in many shapes and forms. They may be done at the individual procedure level (e.g., a bundled payment in a center of excellence) or at the population level, holding providers accountable for the total cost of care and outcomes for a significant group of patients attributed to them (e.g., an accountable care organization.) The scope of patient population and services included in any value-based arrangement will impact how value is determined.

Measuring Quality

There are several groups that create and endorse health care quality measures that are then used to determine the quality of care delivered by providers in value-based arrangements:

- The National Quality Forum (NQF) brings together multistakeholder groups of experts to assess and endorse health care quality metrics; an NQF endorsed measure is generally considered to be scientifically valid.

Measuring Value through an Equity Lens

If an accountable care organization (ACO) performs highly on a quality metric looking at their entire patient population, but the patients who did not receive high-quality care were predominantly racial minorities or low income, would you consider that high-quality care? Arguably not.

Employers should push their provider and health plan partners to parse their data by available demographic information, like race and income, or a proxy, such as zip codes, to identify variations in provider performance across their attributed populations. Employers may want to require a certain level of equity across these demographics for providers to achieve bonus payments for high-value care, even if on average, they performed well.

- The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) created the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS), which are commonly used in value-based contracting.

- The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Measures Inventory lays out every quality measurement that is currently being used or considered for development in various quality, reporting and payment programs.

For value-based arrangements that focus on a specific procedure, such as a COE, many medical societies have standardized quality measures to which physicians who perform these procedures should be held accountable. For example, the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery created the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program, which contains quality measures used for bariatric surgery nationally.

For population-based arrangements, like a high-performance network or ACO, quality metrics are generally more focused on rates of evidence-based services being provided (e.g., the percentage of plan members who received a flu vaccination, rates of cancer or depression screenings, etc.) These metrics often include quality measurements on how efficiently patients are referred to high-performing specialty and outpatient care. See the Medicare Advanced Payment Model Performance measures for 2021 to get a sense of additional measures used.1

Risk Adjustment and Outliers

Risk adjustment refers to the process of adjusting target quality and outcomes goals for value-based contracts based on the prevalence of disease burden and demographics of the patients attributed to participating providers. Risk adjustment is necessary to not disincentivize providers from taking on sicker patients, who may be more difficult to bring to “good health” than someone who is already relatively healthy. In fact, those patients who are sicker tend to have more opportunities for health improvement and cost reduction than healthier individuals.

Value-based contracts may also exclude patients with extremely high-cost conditions from being included in calculations of the cost of care or outcomes measures. For some provider groups under financial risk for the cost of care, a handful of rare but extremely expensive cases could ruin their chances of achieving outcomes and cost goals, even if their performance for the rest of their attributed patient population was excellent. The smaller the patient population that a provider group is responsible for, the more important it is to adjust performance on quality and cost metrics based on patient risk profiles.

Measuring Outcomes

If measuring quality is about what providers do and where, measuring outcomes is about how the patients did based on the quality of their care.

Common outcomes metrics include:

- Hospital readmission rates;

- Rates of avoidable emergency room visits;

- A1c control among patients with diabetes;

- Blood pressure control; and

- Patient safety, such as avoidance of wrong-site surgery.2

Outcomes measures are generally more difficult for providers to impact than quality measures because they are more influenced by incidents that happen outside the provider’s control and their four walls. A hospital readmission, for example, could be due to someone falling while in recovery for surgery, even though the surgery was performed well. Therefore, for providers to impact outcomes metrics, they must reach out and communicate more effectively to patients, caregivers, and other providers outside the their setting of care. This may require more effort, but it is worth it to achieve positive outcomes and accomplish the ultimate goal of medical care – helping people be healthy.

Measuring Patient Experience

Patient experience is measured in several ways, the most common of which is the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) created by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.3 CAHPS surveys are sent to patients who have received care in hospitals, clinical practices, and surgery centers. These surveys are comprehensive, but are generally done by mail and are lengthy, which depresses the rates of patients who actually complete them. The incorporation of virtual care into standard medical practice has made capturing patient experience of care easier because it can be incorporated directly into digital processes, eliminating the need for physical mail.

Ditching Discounts as a Measure of Value: The Promise and Challenge of Total Cost of Care

The level of discounts off a providers’ list prices is often used as a comparison tool for the strength and competitiveness of a health plan’s network and contracted rates. However, the lowest discount percentage does not necessarily mean lowest net cost, as list prices can vary. More importantly, discounts do not demonstrate how well a health plan is able to hold down the total cost of care through value-based contracting or offering a higher quality of providers within the network. Providers or provider groups and their health plan partners able to manage the total cost of care they deliver, while also achieving quality, outcomes and experience standards, are more desirable than others who accept a deeper discount on each service.

Common patient experience measurements include positive feedback from patients on questions like:

- Did my clinician provide care that aligned with my cultural beliefs and goals?

- Did my clinician clearly communicate my treatment options and listen to my concerns?

- How long did it take to get an appointment with my provider?

- How likely is it that you would recommend your [doctor/hospital] to a friend or colleague? (i.e., their net promoter score)

Measuring Total Cost of Care

The total cost of care seems like it should be a simple sum of all claims costs associated with a person’s care, but unfortunately, it gets more complicated quickly. Some of the key considerations when determining the total cost of care as an outcome measure include:

- Will pharmaceutical spending be included? Part 2: Value-Based Reimbursement Strategies discusses this question in greater depth.

- Will per-member per-month (PMPM) fees paid by employers to providers to help them invest in resources to deliver value-based care and patient support services be included in the total cost?

- For value-based arrangements for discrete procedures (e.g., a bundled payment for a heart surgery,) which services before, during and after the procedure will be included in the measurement of its cost?

- Similarly, which costs are associated with the care related to the procedure and which are not? Cost calculations can get messy when you’re parsing claims data related to a surgical episode amid other unrelated claims costs.

- Do costs associated with third-party vendors interacting with employees outside their standard clinical relationship count in the cost equation?

- For value-based arrangements focused on primary care, which costs are considered to be within a primary care provider’s control and which are not for the purposes of total-cost-of-care measurement?

- Are other related costs impacted by higher quality health care going to be included in the calculation, such as employee productivity or economic burden on caregivers?

Employers, in partnership with their health plans and provider partners, will need to answer these and other questions as they determine how costs will be defined and which will be included in calculations of value.

Improving on Trend as a Measure of Performance

In many cases, value-based contracting – especially as it relates to performance on controlling costs -- will be based on trend guarantees rather than on an absolute reduction in costs, for example. If a provider group and/or health plan is able to keep year-over-year cost trend at 2% when similarly situated providers/plans are delivering 6% increases, this can have a huge financial impact for employers and their employees. Many contracts will have historical claim lookbacks for a few years to establish a baseline cost trend, then hold providers and/or health plans responsible for mitigating increases to that trend going forward.

Conclusion

When talking about value-based health care, it is often easier to start with what the ideal delivery of care would be and then work backward from there to determine how payments will facilitate and incentivize that delivery standard. Defining quality care, desired health outcomes, patient experience standards, and how your costs will be measured is vital for effective value-based purchasing.

Employer Recommendations

- 1 | Before assessing value-based care opportunities, consider which health challenges in your employee and dependent populations you are looking to solve and what existing care gaps are impacting certain groups of patients.

- 2 | Keep in mind that the value equation includes both a numerator and a denominator. A value-based care strategy that improves quality outcomes, and experience while holding costs steady increases value even without a measurable cost reduction in the short run. Of course, willingness and ability to invest time into value-based purchasing initiatives that do not have short- or medium-term cost savings will vary by employer.

- 3 | Determine your timeline for value creation. Value-based care efforts by health care providers may take more than 1 year to bear fruit, especially for population-level approaches. Even within a plan year, assessing total cost of care associated with procedure-level value-based reimbursements, such as a bundled payment, will likely take longer than the standard fee-for-service claims to be reported to employers.

- 4 | Consider how unanticipated and/or expensive clinical innovations that arise during the contracted period will be handled in cost calculations. You will need to align with your partners about how to handle such a case (e.g., hepatitis C treatments that were incredibly effective but unexpectedly spiked health care costs in 2014-2016.)

- 5 | Align with your health plan and provider partners on how value-based care performance will be attributed if a patient is cared for by multiple providers. For instance, is an ACO contracted for the cost and performance outcomes of a patient population responsible for patients who receive surgical care in a separate employer Center of Excellence COE travel program? In some cases, a third-party COE provider may achieve better outcomes on average than a given ACO, thereby benefiting that ACO in total cost of care and outcomes calculations, but what if that doesn’t happen? Should the ACO be penalized for subpar care delivered by another provider group?

More Topics

Articles & Guides- 1 | Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Performance Year 2021 APM Performance Pathway: CMS Web Interface Measure Benchmarks for ACOs. Quality Payment Program. Accessed October 11, 2022. https://qpp-cm-prod-content.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/1306/Performance%20Year%202021%20APM%20Performance%20Pathway-CMS%20Web%20Interface%20Measure%20Benchmarks%20for%20ACOs.pdf

- 2 | The Leapfrog Group. Preventing and Responding to Patient Harm. Leapfrog Ratings. Accessed October 11, 2022. https://ratings.leapfroggroup.org/measure/hospital/preventing-and-responding-patient-harm

- 3 | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. About CAHPS. July 2022. Accessed October 11, 2022. https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/about-cahps/index.html

- 4 | Conti R et al. Projections of US Prescription drug spending and key policy implications. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(1). https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama-health-forum/fullarticle/2776040. Accessed November 8, 2022.

- 5 | Business Group on Health. Emerging Trends in Cancer Care. October 25, 2021. https://www.businessgrouphealth.org/resources/emerging-trends-in-cancer-care. Accessed November 8, 2022.

- 6 | Golden W et al. Changing how we pay for primary care. New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst. November 20, 2017. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0326. Accessed November 8, 2022.

- 7 | Bitton A et al. Off the hamster wheel? Qualitative evaluation of a payment-linked patient-centered medical home (PCMH) pilot. The Milbank Quarterly. 2012 Sep; 90(3): 484–515. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3479381/. Accessed November 8, 2022.

- 8 | Primary Care for Boeing’s Mesa Employees. Iora Health. Accessed on February 9, 2022. https://ioraprimarycare.com/boeing/

- 9 | Bleser W, et al Half a decade in, Medicare accountable care organizations are generating net savings: Part 1. Health Affairs Blog. September 20, 2018. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20180918.957502/full/. Accessed November 8, 2022.

- 10 | Sullivan G, Feore J. Physician-led accountable care organizations outperform hospital-led counterparts. Avalere. October 15, 2019. https://avalere.com/press-releases/physician-led-accountable-care-organizations-outperform-hospital-led-counterparts. Accessed November 8, 2022.

- 11 | Business Group on Health. 2023 Large Employers’ Health Care Strategy and Plan Design Survey. https://www.businessgrouphealth.org/resources/2023-plan-design-health-care-delivery-system. Accessed November 8, 2022.

- 12 | Lapsey H. The Better Benefit Stack. 2018 Oliver Wyman Health Innovation Journal. https://health.oliverwyman.com/2019/03/the-better-benefit-stack.html

- 13 | Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Shared Savings Program Continues to Grow and Deliver High-Quality, Person-Centered Care Through Accountable Care Organizations. CMS Newsroom. January 26, 2022. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/medicare-shared-savings-program-continues-grow-and-deliver-high-quality-person-centered-care-through. Accessed November 8, 2022.

- 14 | O’Reilly K. Doctor participation in ACOs, medical homes grows amid pandemic. American Medical Association. December 7, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/payment-delivery-models/doctor-participation-acos-medical-homes-grows-amid. Accessed November 8, 2022.

- 15 | Avalere. MSSP Sees Continued Growth in Downside Risk ACOs. January 21, 2020. https://avalere.com/insights/mssp-sees-continued-growth-in-downside-risk-acos. Accessed November 8, 2022.

- 16 | Mechanic R et al. The 2018 Annual ACO Survey: Examining the Risk Contracting Landscape. Health Affairs Forefront. April 23, 2019. https://wwwhealthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20190422.181228/full/. Accessed November 8, 2022.

- 17 | Business Group on Health. 2023 Large Employers’ Health Care Strategy and Plan Design Survey. https://www.businessgrouphealth.org/resources/2023-large-employers-health-care-strategy-and-plan-design-survey

- 18 | Business Group on Health. 2023 Large Employers’ Health Care Strategy and Plan Design Survey. https://www.businessgrouphealth.org/resources/2023-plan-design-health-care-delivery-system.

- 19 |Elkins K. Lowe's free surgery program helps cut costs, benefit employees. Charlotte Business Journal. March 30, 2016. https://www.bizjournals.com/charlotte/blog/outside_the_loop/2016/03/lowe-s-free-surgery-program-helps-slice-costs.html. Accessed November 8, 2022.

-

IntroductionValue-based Purchasing Employer Guide: Introduction

-

Executive SummaryValue-based Purchasing Employer Guide: Executive Summary

-

Part 1Definitions and Measures of Value in Value-based Purchasing

-

Part 2Value-based Reimbursement Strategies

-

Part 3Value-based Primary Care

-

Part 4Accountable Care Organizations and High-Performance Networks

-

Part 5Centers of Excellence

-

Part 6Value-based Virtual Care

-

Part 7Value-based Care Engagement Strategies

This content is for members only. Already a member?

Login

![]()