May 15, 2020

The following is intended to provide a basic overview of rebates as well as considerations for employers who are looking to understand the steps and implications involved with passing them forward to members at the point of sale (POS).

The Rebate: A Quick Breakdown

A prescription drug rebate is a “price concession paid by a pharmaceutical manufacturer to the health plan sponsor or the PBM working on the plan’s behalf.” 1 Typically, rebates are paid to the PBM, who then shares a portion with the plan sponsor. Rebates paid to a PBM or health plan are known to influence formulary tier placement for the pharmaceutical manufacturer’s product, which, in turn, may dictate copay and/or coinsurance amounts for patients. This practice leads to an escalation in gross drug prices, where manufacturers set high list prices to withstand offering higher rebates and maintain a profit.2 Additionally, each stakeholder within the supply chain (i.e., manufacturer, wholesaler, PBM, health plan and pharmacy) is often paid based on a percentage of list price, meaning that the entire supply chain profits from, and thus contributes to, this price escalation. The rebate practice may also limit patients’ access to cheaper medications if the post-rebate net price of the drug falls below the list price of more affordable options (i.e., lower cost brands or even generics), keeping them off formulary altogether – yet another price escalation pressure point.3 The latter point also has concerning long-term pricing implications, given reduced market incentives for the continued development of generic products.

Negotiated rebates are, on average, approximately 30% of the list price (or gross price); however, this often differs by drug type.4 Rebates are highest and most commonly associated with brand drugs in competitive therapeutic classes, where alternative, more affordable treatments are available.3 A Medicare Part D study revealed that rebates averaged 39% of gross drug price in cases of significant brand competition and a much lower 14% among protected class drugs.4 They are rarely associated with generic drugs.3 Reports indicate that, in general, Medicare Part D sees higher average rebates (31%) than private plans (16%) and that the highest rebates are seen on the Medicaid side (61%), where state governments can tap into “best price” requirements. These numbers and claims, however, have not gone unchallenged. Some sources, for instance, have found lower brand drug rebates on the Medicare side than in the private sector. Additional sources reveal that the average rebate on a branded drug can also vary based on whether the drug is administered under the medical benefit or through outpatient prescription drug coverage.4 For employers, the rebate’s impact on overall drug spend also varies depending on their drug mix and how their PBM approaches drug price negotiations (i.e., depending on whether the PBM prioritizes rebates over discounts).

A Shift in Status Quo?

Historically positioned as a mechanism to keep the overall cost of drugs low, rebates have become more widely viewed as a contributor to high and escalating drug prices. As noted at the outset, first, the rebate creates an incentive for manufacturers to set high upfront prices. Second, the perverse incentives within the supply chain contracting model continuously increase drug expenditures because stakeholders are often paid as a percentage of the gross price. Compounding this issue, the supply chain model has not kept pace with plan design changes, also resulting in increased patient out-of-pocket (OOP) expenses.1

This increased focus on the inflationary effects of prescription drug rebates throughout the entire supply chain, both in terms of price setting and price inflation, has led to mounting pressure for change.

- Plan sponsors: In the Business Group’s 2019 Large Employers’ Health Care Strategy and Plan Design Survey, the majority (75%) of employers said they do not believe drug manufacturer rebates are an effective tool for helping to drive down pharmaceutical costs.

- Policymakers: The Trump Administration targeted rebates as part of its 2018 “American Patients First Blueprint to Lower Drug Prices and Reduce Out-of-Pocket Costs” with a proposal to exclude rebates from safe harbor protections and require that they be passed on to patients at the pharmacy counter. Although the proposal was withdrawn after the Congressional Budget Office estimated that it would increase federal (Medicare and Medicaid) spending by more than $177 billion dollars over the next decade, political pundits suspect that there will be similar future regulatory and legislative proposals.5

- PBMs: Organic industry evolution to address widespread criticism of the rebate’s impact on drug prices and the need for more transparency is ongoing. New PBM models have entered the market in recent years and notably represent a deviation from the traditional spread pricing model. Instead, they derive revenue exclusively from administrative fees and promise 100% pass-through of all pharma-generated revenue to the client. These new models seem to have influenced reform from traditional players as well. For example, both CVS and Express Scripts announced that they have de-emphasized the importance of rebates in their business model.4

Despite growing prevalence of “100% pass-through” guarantees, some critics are skeptical of full transparency claims. Payments from the manufacturer to the PBM can include administrative service fees, price protection guarantees and other discounts based on market share or patient outcomes. Contract language on these other revenue streams is opaque and does not specify what portions of this additive revenue is being passed through to plan sponsors. In addition, rebate guarantees vary by contract and can be based on a PBM’s book of business or limited to “client-specific” rebates. Many argue that pass-through arrangements have done little to solve the overarching issue of high list prices and have instead resulted in PBMs shifting to alternative methods to charge for their services.4

- Manufacturers. On the other end of the pharmaceutical supply chain, drug manufacturers maintain that PBMs and payers are not passing rebates along to patients and argue that OOP costs and retention of rebates by middlemen – not drug prices – are responsible for fueling the sticker shock that is taking place at pharmacy counters across the country.6

Point-of-Sale Debate

Historically, savings realized from manufacturer rebates have been used by plan sponsors to reduce total plan costs and lower employee premiums for all beneficiaries. In recent years, point-of-sale (POS) rebates were introduced by PBMs as a potential solution to member cost escalation. The POS model offers a way to share plan-negotiated rebates with members, treating rebates the same as discounts and recognizing the need to address spread pricing within the high deductible health plan (HDHP) construct.

However, as evidenced by our most recent 2020 Large Employer’s Health Care Strategy and Plan Design Survey, the majority of surveyed employers believes that the POS model fails to address market incentives that increase drug prices. Additionally, many plan sponsors have highlighted the potential for POS rebates to ultimately raise costs to members because total plan costs, and therefore premiums, will inevitably increase.

Though hopeful that comprehensive solutions for a more sustainable drug pricing and delivery model come to bear, employers recognize the near-term importance and urgency of mitigating OOP prescription drug expenses for employees. Our abovementioned survey revealed that:

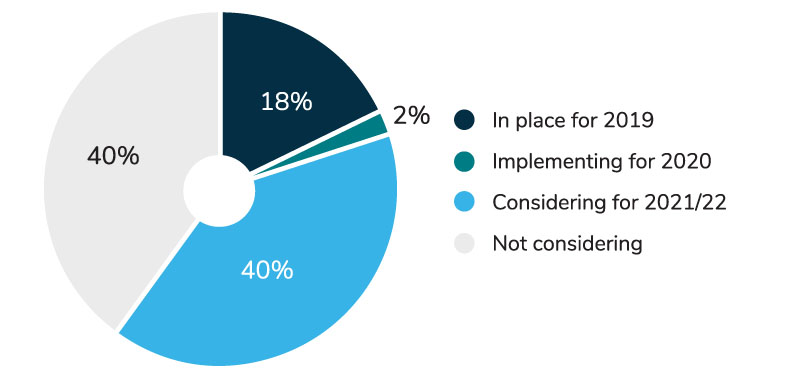

- Nearly 60% of employers either have a POS program in place or are considering implementing one in the next 3 years (Figure 1).

- For the 40% of large employers who are still contemplating a POS rebate program, their greatest challenge lies with determining how to financially account for the shift of rebate value from an overall plan benefit (reducing costs to all employees) to one that more precisely benefits those members filling rebate-enabled prescriptions.

- According to employers that already have a program in place, a variety of cost-sharing options have been adopted to address this challenge:

- 29% of employers absorbed the increased costs;

- 17% shared costs between the employer and the employee through premium increases; and

- 10% shifted the costs through increased employee contributions, copays, coinsurance and deductibles.

Considerations

- 1 | The growing level of rebates, and impact to overall dollars, makes this an increasingly material issue.

- 2 | That said, only 8%-10% of drugs are rebatable; therefore, the decision to move to a POS model benefits a small number of members, while keeping rebates in the plan reduces premium costs for all.

- 3 | POS rebates ease the pressure of OOP cost for members with high deductibles and high coinsurance for specialty drugs. As such, there is potential for improvement in patient adherence rates.7

- 4 | However, implementation of a POS model, which may reduce OOP costs for certain plan members and potentially increase their respective adherence, does not have any impact on drug price and may actually contribute to further price inflation over time.

Recommendations

Employers should maintain an expectation that their plan partners will work toward more comprehensive solutions for managing drug prices, including assessing specialty pharmacy management options, site-of-care management and improved management of drugs administered through both the medical and pharmacy benefits. Employers should also continue to request information on enhanced approaches to transparency and alternative, more efficient, drug formulary, payment and delivery models. Specifically, employers should:

- Evaluate how total plan costs, cash flow and employee premiums would be impacted by migrating to a POS rebate model.

- Ask plan partners for complete transparency on associated rebate administration fees and whether the transition would prompt additional or new fees.

- Understand their PBM’s estimation methodology and proposed retroactive validation and distribution of rebates, since plan rebate levels may be based on annual drug volume and calculated well after the member has left the pharmacy.

- Discuss the process for reporting and monitoring data with their PBM. Request details on how their PBM will administer the POS process, what the rebate percentage shared vs. trued up at the end of the year will be, and the timing of this true-up. NOTE: The percentage passed through to the employee may be customized at the employer’s discretion (this may vary by PBM).

- Understand the cost of managing the POS rebate program that will be assessed by their PBM and its impact on administrative fees.

Drive change with our Pharmacy Benefit Committee.

Learn More ![]()

A World Beyond Rebates?

While an effective mechanism for lowering patient OOP costs, POS rebates do little to solve the central issues – high and escalating drug prices and an outdated pharmaceutical supply chain contracting model that compounds high prices by incentivizing highly rebated drugs. An alternative model based on net price of medications with no rebates would be welcomed by many employers – two-thirds, according to our 2020 survey (67%). In a June 2018 Senate committee hearing, U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar proclaimed that “right now, everybody in the system makes their money off a percentage of list price” and that “we may need to move toward a system without rebates.”

What would a world without rebates look like? The reality seems to be that plan costs in the short term would increase. Even in the long term, we’d find many of our drug pricing issues left unsolved. For instance, some of the most expensive drugs on the market are the ones that have little to no competition and were never rebated to begin with.2

In the meantime, while we work to transform the current model, the Administration and Congress are exploring additional drug pricing options, including, but not limited to, policies to bring more generic drugs to market, importing prescription drugs from other countries, establishing an international pricing index and allowing the federal government to negotiate drug prices under Medicare Part D.

- 1 | Dusetzina SB, Conti RM, Yu NL, Bach PB. Association of prescription drug price rebates in Medicare Part D with patient out-of-pocket and federal spending. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2017;177(8): 1185–1188. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5722464/. Accessed April 14, 2020.

- 2 | Thomas K. Meet the rebate, the new villain of high drug prices. The New York Times. July 27, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/27/health/rebates-high-drug-prices-trump.html. Accessed April 14, 2020.

- 3 | Alston M, Dieguez G, Tomicki S. A primer on prescription drug rebates: Insights into why rebates are a target for reducing prices. 2018. Milliman. https://www.milliman.com/en/insight/a-primer-on-prescription-drug-rebates-insights-into-why-rebates-are-a-target-for-reducing. Accessed April 14, 2020.

- 4 | Cole A, Towse A, Segel CS, Henshall C, Pearson SD. Value, access, and incentives for innovation: Policy perspectives on alternative models for pharmaceutical rebates. ICER. March 2018. https://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/March-2019-ICER-OHE-White-Paper-on-Rebates-Final.pdf. Accessed April 14, 2020.

- 5| Berson SW, Carnegie TC, Mora MS. Trump Administration withdraws proposed rebate rule. National Law Review. July 11, 2019. https://www.natlawreview.com/article/trump-administration-withdraws-proposed-rebate-rule. Accessed April 14, 2020.

- 6| Roland D. Sanofi, fighting back in insulin price debate, says its net prices fell 11%. The Wall Street Journal. March 4, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/sanofi-fighting-back-in-insulin-price-debate-says-its-net-prices-fell-11-11583340721. Accessed April 14, 2020.

- 7| UHC. Expanded point-of-sale discount program to lower prescription drug costs for more consumers. United Healthcare Newsroom. March 12, 2019. https://newsroom.uhc.com/affordability-/prescription-drug-discount-program.html. Accessed April 14, 2020.

More Topics

Articles & Guides

This content is for members only. Already a member?

Login

![]()